Hamzah Khan: social services missed warning signs, report finds

Serious case review follows conviction of Hamzah's mother, Amanda Hutton, who was found guilty of his manslaughter

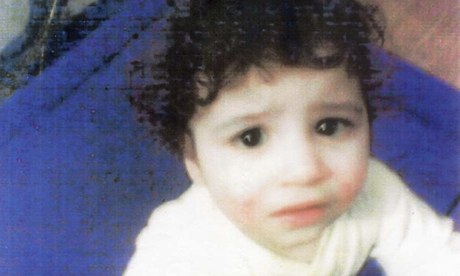

Hamzah Khan, whose body lay undiscovered for almost two years after he was allowed to starve to death by his mother. Photograph: West Yorkshire police/PA

An older brother of an "invisible" boy starved to death by their mother in Bradford complained to police and social services about physical and emotional abuse in the family home three years before the little boy died, an independent report has found.

A serious case review (SCR) into the starvation of four-year-old Hamzah Khan has concluded that while his death was "not predictable", Bradford social services missed signs that, had they been put together, could have warned that Hamzah and his seven siblings were at risk.

Last month, Hamzah's mother, Amanda Hutton, 44, was found guilty of his manslaughter and of neglecting six of her eight children. When Hamzah's partially mummified body was found in September 2011, almost two years after his death in December 2009, aged four, he was wearing a Babygro meant for a child aged six to nine months.

Neither he nor any of his siblings was on social services' "at risk" register. Two months before his death he and his family had been struck off their GP's list for persistent non-attendance.

Hamzah was "unknown and invisible to services throughout his short life", receiving no inoculations or help from early years, education or health services almost from birth, the SCR authors write. Like Victoria Climbié, the eight-year-old girl tortured and murdered by her great-aunt in London in 2000, he had not been registered with a GP. As in the Climbié case, and that of Baby P, 17-month-old Peter Connelly, who died in 2007 after being abused by his mother and her partner, there were insufficient challenges to Hamzah's mother when she refused help.

Hutton's deliberate decision to withdraw him from all of the usual and universal services was a significant factor in both his death and why she was able to hide it for so long, the report says.

While not blaming any one agency for failing Hamzah, the authors make 50 recommendations for "learning", which have been accepted by the Bradford safeguarding children board.

The independent experts examining Hamzah's case also found that in late 2006, when Hamzah was one-and-a-half, one of his older siblings went to the police complaining that both Hutton and her partner, Aftab Khan – father to all eight children – had assaulted him.

Police used their powers of protection to try to arrange safe accommodation with Bradford children's social care (CSC). But they were unable to find a placement and the boy returned home.

The boy made another complaint of physical and emotional abuse in May 2007 although at the time it was interpreted by social workers as being "teenage angst" rather than something more serious. He spent two nights in emergency accommodation before being returned back to the family home by the end of the month.

Amanda Hutton outside court during her trial. Photograph: Anna Gowthorpe/PA

Amanda Hutton outside court during her trial. Photograph: Anna Gowthorpe/PA

Two years later Hamzah was dead, left to rot in his cot, his siblings told to lie to everyone and say he had moved to Portsmouth.

The family had received help from a host of agencies, including the police, probation service, a domestic violence charity called Staying Put, the Yorkshire ambulance service, Bradford children and young people's services and Bradford early years children's services as well as various health services. They were also the subject of a so-called Marac, a multi-agency risk assessment conference. Many referrals were made to CSC from a number of these agencies, but the children were never assessed as being of significant risk of harm.

All of the agencies focused their efforts on Hutton as a victim of domestic violence, rather than her children, the SCR panel found. The experts report that while much help was offered to Hamzah's mother, who was beaten up by her partner for much of their 22-year relationship, not enough focus was put on whether her children were safe and well.

The SCR authors found that Hutton's reluctance to accept help was poorly understood and that insufficient attention was given to the implications of factors such as domestic violence and substance misuse on the children and their emotional as well as physical care and wellbeing.

A police officer who did gain access to Hutton's house in the March before Hamzah died reported that her children seemed safe and well, despite at least one child not having a bed to sleep in.

But this assessment, along with others, only addressed that the children did not appear to be physically at risk rather than offering clearer insight into the emotional and psychological impact of their turbulent family life.

The SCR also found that social workers were too ready to accept Hutton's word when she refused intervention or support, missing appointments and refusing access to the family home.

A "more assertive" approach, the authors write, would have given more explicit consideration to the needs of the children and probably sought to override parental objections including if it had been necessary and subject to legal advice, going to court for an appropriate order. Legal options were not considered because key services never believed that the children were suffering harm at the time.

Hutton withdrew increasingly from any contact with services after Hamzah's birth for a variety of complex reasons, the SCR authors write.

"A contributory factor appears to be the degree of domestic violence she suffered and the social isolation she felt. Associated with this was the reaction from some people in the community to a relationship that involved partners from different cultures and religions.

"Hamzah was invisible to services largely because neither of his parents participated in the routine processes such as ensuring he saw health professionals on a regular basis or was enrolled for early years to educational provision."

The SCR said the various agencies did not share information readily enough. "The lack of joined up assessment, information-sharing and thinking, meant there were missed opportunities for multi-agency action to help this family and protect the children," the authors write.

They also noted that at the time of Hamzah's death, children's social services were struggling to cope with the significant increase in referrals that followed from the publicity of the Baby P trial in 2008.

The SCR panel said they had found no information that suggested there was one opportunity for a single individual to have saved Hamzah. Their conclusion was there were a "constellation of factors" that contributed to his death.

The SCR identified examples of good practice among the Bradford authorities that had contact with Hutton and her family. These included:

• The police, who took prompt action when one of the children asked for help because of the domestic violence; this included ensuring CSC became involved.

• The registrar who made a home visit to register the birth of one of Hutton's youngest children.

• The police officer who gained the trust of Amanda Hutton tried to secure effective help and support in response to the domestic violence which included referral to housing and specialist advice services.

• The ambulance crew ensured that their concerns about the welfare of children was reported to CSC when they were called to the house.

• The school nurse tried to make a home visit when she was concerned about lack of contact.

• The police community support officer whose "very considerable persistence in gaining access to the house in 2011" led to the discovery of Hamzah's body.

Responding to the review on Wednesday, Dame Clare Tickell, chief executive at Action for Children, said it was vital experts listen to children rather than just adults

"Children at risk of dying at the hands of their parents are crying out for help but they aren't being heard.

"More support for professionals who work with neglected children is vital; they must be allowed to trust their instincts and escalate their concerns.

"Social workers, teachers and police officers have told us about the barriers they face when they want to help a child who they suspect is being neglected. It seems that people are so afraid of doing the wrong thing, they don't do anything, which adds up to a systemic failure to protect the most vulnerable.

"We all need to be allowed to be braver; to push harder by being persistent and take action to protect children, or child neglect will continue to have devastating effects."

No comments:

Post a Comment